Archaeologists rediscovered the 12th-century altar in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where tourists had unknowingly covered its backside in graffiti.

Archaeologists Rediscover A Lost Crusader Altar

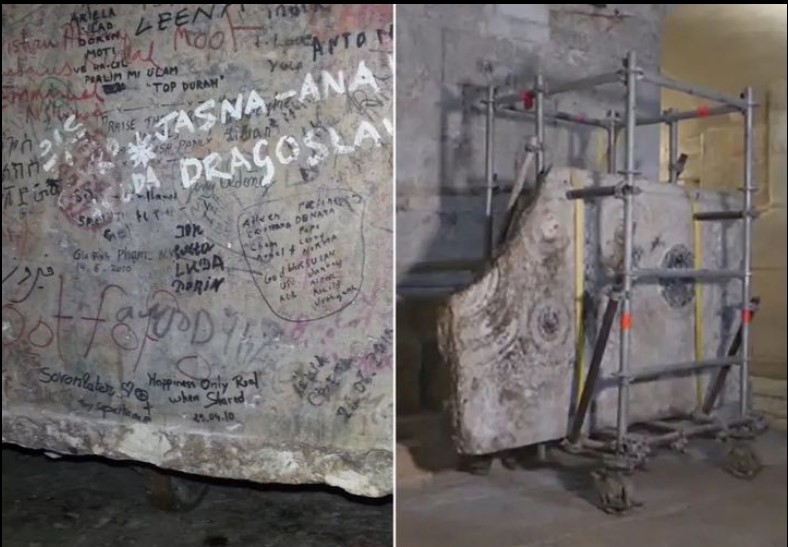

In 2018, archaeologists working inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem made a startling discovery. While examining a rear corridor of the ancient church, they noticed a large stone slab casually leaning against a wall. For years, tourists had passed by and scribbled graffiti across its exposed surface, unaware that they were marking one of the church’s long-lost treasures.

When the researchers turned the slab over, the truth became immediately clear: this was the missing Crusader-era altar, believed for centuries to have been destroyed.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built in the 4th century over what Christians believe to be the site of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion and burial, has been extensively modified throughout its history. But the altar’s location had long confounded historians. Pilgrim accounts described a magnificent marble altar present in Jerusalem in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, yet it vanished from all records by the 19th.

For decades, scholars assumed it had perished in an 1808 fire that devastated part of the church.

Instead, it had been hiding in plain sight.

“The fact that something so important could lie undetected in this place for so long was completely unexpected for everyone involved,” said historian Ilya Berkovich of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

A Roman Masterpiece Crafted For Jerusalem

The altar dates back to 1149, during a period when Christian Crusaders controlled Jerusalem. What makes it especially significant is its construction: it was made using Cosmatesque, a medieval mosaic technique practiced almost exclusively by Roman master craftsmen.

In a recent statement, the Austrian Academy of Sciences explained the method:

“The technique was characterized by the fact that its masters could decorate large areas with small amounts of the precious marble… by assembling small marble splinters with the greatest precision and attaching them to stone supports to create geometric patterns and dazzling ornaments.”

The altar’s elaborate circular motifs symbolized themes central to Christian theology, including the infinity of God’s creation, the wounds of Jesus, and the Jerusalem Cross. Its sophistication and style point to an extraordinary conclusion:

a Roman master artist was sent to Jerusalem specifically to create it.

This is only the second known Cosmatesque altar ever found outside Italy, underscoring the unique artistic exchange between medieval Rome and the Holy Land.

The discovery significantly expands historians’ understanding of cross-Mediterranean craftsmanship during the Crusader period. Far from being isolated, Jerusalem was part of a vibrant network connecting Europe’s artistic and religious centers.

Why The Altar Was Built, And Why It Disappeared

According to Christian tradition, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands atop the tomb where Jesus Christ was buried. Its location has made it one of the most revered sites of Christianity for nearly 1,700 years.

Following the First Crusade and the Siege of Jerusalem in 1099, Crusader rulers renovated and expanded the church. The newly rediscovered altar was installed around 1149, marking the 50th anniversary of the Christian conquest.

For centuries, pilgrims described the altar in glowing terms. Yet sometime after the 18th century, references to it abruptly stop. Historians believed the 1808 fire had destroyed it, a logical conclusion, given the scale of the damage.

But the slab’s survival raises new questions:

- Who moved it?

- Why was it placed face-in against a wall?

- How did centuries of researchers miss it?

Despite millions of annual visitors and numerous archaeological surveys, the altar remained unidentified. Its placement in a back corridor, far from public view, protected it from scrutiny but exposed its reverse side to tourists, who unknowingly covered it in modern graffiti.

Whether its relocation was accidental, intentional, or part of a now-forgotten restoration effort remains a mystery.

What This Discovery Reveals About Medieval Jerusalem

The presence of a Cosmatesque altar in Jerusalem has profound implications. The technique was highly specialized, requiring artists trained in Rome’s guild workshops. As the Austrian Academy of Sciences notes, these craftsmen typically repurposed precious marble from ancient Roman ruins to create their intricate geometric designs.

That such expertise was brought to Jerusalem suggests:

1. A Direct Artistic Link Between Rome And The Holy Land

This altar may be evidence of official papal involvement in the church’s restoration, perhaps even an explicit commission from Rome to enhance the spiritual prestige of the site.

2. Jerusalem’s Elevated Status In The 12th Century

Crusader kings and bishops aimed to transform the city into the beating heart of Christendom. Importing Roman artistry helped signal its renewed importance.

3. Active Cultural Exchange Across Crusader Territories

Despite ongoing conflict, skilled workers, trade goods, and artistic traditions continued to circulate widely between Europe and the Middle East during the Crusader era.

These findings reposition Jerusalem not as a remote frontier but as a key cultural crossroads.

The Rediscovery’s Impact On Historical Scholarship

The Austrian Academy of Sciences team continues to study the altar closely. Their research is helping reconstruct how Crusader artisans combined local and imported design traditions, and how the church’s interior evolved in the centuries following the Crusades.

Additionally, the slab, once ignored, mislabeled, or simply overlooked, is now recognized as a major medieval artifact. Its rediscovery offers scholars a rare, tangible link to the artistic world of 12th-century Jerusalem.

As Berkovich emphasized, the find challenges long-standing assumptions:

“Something so important lying undetected for so long” underscores how much remains hidden even in sites that have been studied for centuries.

A Lost Masterpiece Returns To The Light

After centuries of obscurity, the Crusader altar is finally being examined, documented, and conserved. Its modern graffiti, ironically, part of the reason it was ignored for so long, will be carefully addressed, though conservators must determine whether to remove or preserve the markings as part of its unusual modern history.

For now, what matters most is that the slab has emerged from the shadows. A key piece of Jerusalem’s Crusader past, and a rare bridge to Roman master craftsmanship, is once again visible.

Its rediscovery reminds us that even in the world’s most studied sacred spaces, history still hides in plain sight.

Featured image from: Old photo archive