DIPG used to be a death sentence. Now, for the first time, there’s hope.

A Miracle No Doctor Saw Coming

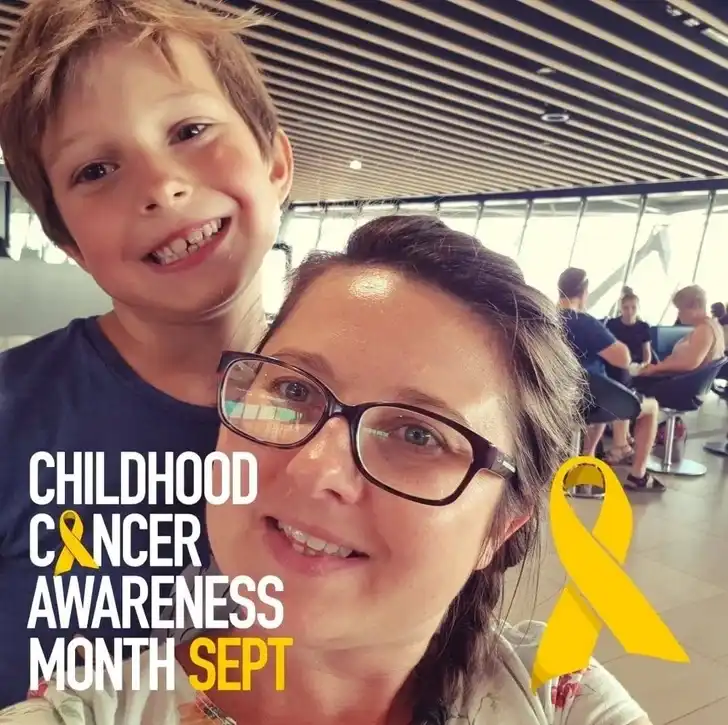

It’s every parent’s worst nightmare: hearing that your child has a fatal illness and there’s nothing doctors can do. For the family of Lucas Jemeljanova, a young boy from Belgium, that nightmare began when he was just six years old.

Lucas was diagnosed with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), one of the most aggressive and deadly brain cancers known to medicine. Found primarily in children, DIPG grows in the brain stem, the area responsible for vital functions like breathing and heartbeat.

For decades, DIPG has carried a near-100% fatality rate. Fewer than 10% of children survive two years after diagnosis. Even with radiation and chemotherapy, the tumors are nearly impossible to remove.

So when Lucas’ parents, Cedric and Olesja, heard the diagnosis, they were told to prepare for the worst. But instead, they searched for a miracle, and found one in France.

The Clinical Trial That Changed Everything

Determined to try anything, Lucas’ family flew him to Paris to participate in a clinical trial called BIOMEDE, led by Dr. Jacques Grill at the Gustave Roussy Cancer Research Institute, one of Europe’s leading pediatric oncology centers.

The BIOMEDE trial tested new drugs against DIPG, each targeting a different biological pathway. Lucas was randomly assigned to receive everolimus, a chemotherapy drug already used to treat breast, kidney, and pancreatic cancers, but never before tested on DIPG.

“Over a series of MRI scans, I watched as the tumor completely disappeared,”

said Dr. Grill in an interview. “And it has not returned since.”

What began as a desperate attempt soon became history in the making.

How Everolimus Works, and Why It Succeeded

Everolimus works by blocking a protein called mTOR, which helps cancer cells divide and grow new blood vessels. By inhibiting this process, the drug effectively starves tumor cells, stopping them from spreading.

Lucas’ doctors believe his extraordinary response was linked to a rare genetic mutation in his tumor that made its cells unusually sensitive to everolimus.

“We think that this mutation made the tumor far more responsive to the drug,” said Dr. Grill. “Other children also benefited, but Lucas’ case was unique.”

Seven other patients in the BIOMEDE trial were labeled “long responders”, their tumors stopped progressing for over three years, but Lucas’ complete remission remains unmatched.

Even after his tumor vanished, Dr. Grill continued Lucas’ daily treatment for several years.

“I didn’t know when to stop, or how, because there was no other reference in the world,” he admitted.

From Death Sentence to Hope

Before Lucas, no one had ever survived DIPG. Now, for the first time, doctors have proof that remission is possible.

Dr. Grill’s colleague, Marie-Anne Debily, a senior researcher in the BIOMEDE project, said the discovery is reshaping how scientists approach DIPG.

“Lucas’ case offers real hope,” Debily said. “We need to understand exactly why it worked, and how to reproduce that success.”

The team’s next step involves studying tumor organoids, tiny, lab-grown replicas of brain tissue that mimic real tumor behavior. If researchers can replicate Lucas’ response in these models, they could uncover new drugs or combination therapies capable of targeting DIPG at the molecular level.

A Global Search for a Cure

While Lucas’ story stands as a world first, he’s not entirely alone.

Another young patient, identified only as Drew, has also shown remarkable recovery after receiving a new immunotherapy treatment in a separate clinical trial. Drew’s tumor disappeared and has stayed gone for more than four years, suggesting that breakthroughs in DIPG treatment may finally be within reach.

Recent trials exploring CAR-T cell therapy and targeted gene editing have shown early promise as well, giving researchers hope that DIPG, once considered untreatable, may one day have an effective, replicable cure.

What Is DIPG?

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a rare and aggressive brain tumor that primarily affects children between the ages of 5 and 10. The tumor forms in the pons, a part of the brain stem that controls breathing, heart rate, and motor function.

Because of its delicate location, surgical removal is nearly impossible. Treatments usually focus on symptom management rather than cure. Radiation can temporarily shrink tumors, but most patients relapse within months.

Until now, the prognosis has been devastating, with median survival at just 9 to 12 months.

Why This Breakthrough Matters

Lucas’ case could mark a turning point in pediatric oncology.

It challenges the long-held assumption that DIPG is incurable, and proves that, with the right genetic and pharmacological match, even the most resistant tumors can respond to treatment.

For families, the discovery brings something far more powerful than data: hope.

“When we started, the only thing we could do was pray for a miracle,” said Lucas’ father, Cedric. “Now, that miracle has a name, everolimus.”

The Road Ahead

Researchers caution that one case doesn’t equal a universal cure.

Everolimus will not work for every child, but it’s a major step forward. Scientists are now analyzing genetic samples from children worldwide to better understand the molecular signature of DIPG tumors that respond to treatment.

Clinical trials are also expanding to explore drug combinations and personalized therapies, potentially transforming how doctors treat rare childhood cancers.

“For the first time, we have a direction,” said Dr. Debily. “We can build from this.”

A Message of Hope for Families

For parents facing the unthinkable, Lucas’ recovery offers something more than just scientific progress, it offers faith in persistence, innovation, and the human spirit.

In Lucas’ own words, shared through his mother:

“I just wanted to get better so I could go back to school and play football.”

Today, Lucas is 13 years old, back in school, and living a normal life, something no one thought possible seven years ago.

Featured Image from Facebook: Olesja Jmljnv